The Buffalo Bills of the 1960s possessed one of the greatest defenses in the entire history of the American Football League, if not all of pro football. The Bills’ defense, which drove the team to three consecutive appearances in the AFL championship game (1964-66) and two league championships (1964-65), was a mishmash of young players, veterans and reclamation projects that worked its magic under the direction of a young genius named Joel Collier. Aside from its impressive record, the Buffalo defense’s greatest bragging point is the incredible streak of 17 straight games it went without giving up an enemy score on the ground. This article will discuss Buffalo’s great AFL defense and that streak.

The coach in charge of the defensive side of the ball for the Bills during this era was Joel D. Collier, a soft-spoken, bespectacled sort who looked more the part of a lab assistant than a pro football coach. Collier, who played offensive end at Northwestern University, was a student of the game, beginning his coaching career in 1957 when he joined Lou Saban’s staff at Western Illinois University. “That was his first job coaching football,” Saban observed. “He worked day and night. He was on that film almost all of the time. That’s where he learned football.” Collier spent three seasons as an assistant with the Leathernecks before moving with Saban to the Boston Patriots of the newly-formed American Football League in 1960, assuming the role of defensive backs coach. When Saban became head coach of the Bills in 1962, he brought much of his staff, including Collier, with him to Buffalo.

Joe Collier

Collier was a mastermind who loved to tinker with formations, blitzes and stunts. The Bills’ defense blossomed under Collier’s watch, and in 1963 it led the team to its first-ever post-season appearance. By 1964, they were the best in the league. Calling the plays in the defensive huddle was middle linebacker Harry Jacobs, who acted as a coach on the field, or, as he preferred to be called, “the quarterback of the defense.” Jacobs was a full member of the defensive game-planning team, often studying film alongside Collier and devising schemes that were to be used against upcoming opponents.

Joe Collier confers with Middle Linebacker

Harry Jacobs prior to the 1965 AFL Title Game.

“Joe broke films down,” Jacobs recalled. “He was the first person to my knowledge that really worked at breaking down each of the plays so I could see how first, second, third, every down and position, what they use, and then make a choice in that situation on the field. In order to do that, I had to know what everybody else did.” This allowed Harry full autonomy in the huddle to make all of the defensive calls without need of consultation with the defensive coordinator prior to every play. If the Bills' defensive record between 1964 and 1966 is any indication, Jacobs was right a heck of a lot more often than he wasn’t.

“No one ever agrees with the signal caller,” said linebacker Mike Stratton, “and the signal caller was Harry Jacobs. He called all of the defenses. He very rarely had any input from the sidelines—he called them all from his own perspective. He did an outstanding job at calling the defenses even though the lineman and defensive backs maybe did not agree with the calls because it put some pressure on them.”

The Bills' basic defensive alignment was the 4-3, with Ron McDole and Tom Day on the ends, Jim Dunaway and Tom Sestak at tackle, Mike Stratton at right linebacker, John Tracey at left linebacker, Harry Jacobs in the middle, Butch Byrd and either Charley Warner or Booker Edgerson at the corners, Gene Sykes or Hagood Clark at left (strong) safety, and George Saimes at right (free) safety. On the field, the formation was called "41 Red," which meant 4 man front with man-to-man coverage.

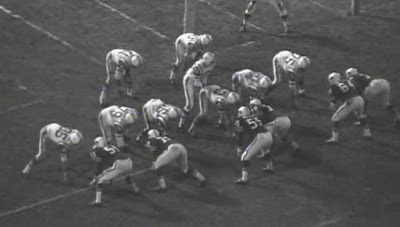

The Bills aligned in their standard 4-3 defense.

Versus New York Jets at War Memorial Stadium,

October 24, 1964.

On occasion, the defense would shift into a 3-4 alignment, which they referred to as the “Oklahoma” formation. The Bills were not the only team to use the 3-4, but they tended to go to it more often than other teams of the era (San Diego, for example). In the Bills’ 3-4, one of the defensive linemen, usually Tom Day but sometimes Ron McDole, would stand up as the fourth linebacker (inside) while Jim Dunaway would move over center.

Buffalo defense aligned in the 3-4, or "Oklahoma"

defense. Tom Day (88) has moved to Right Inside

Linebacker, and Jim Dunaway has moved over

Center. Versus Boston Patriots at War Memorial

Stadium, November 15, 1964.

The Bills in a variation of the 3-4, called

"Oklahoma Inside Up," which featured all

members of the front 7 standing upright at the snap.

Ron McDole (cut off at top) is in at Left

Inside Linebacker. Versus Miami Dolphins at

War Memorial Stadium, November 10, 1968.

On some occasions, one of the linemen would come out of the game and be replaced by a backup linebacker, usually Paul Maguire, and later Marty Schottenheimer.

The Bills aligned in the 3-4 defense with Paul

Maguire (55) in at Left Inside Linebacker. Versus

New York Jets at War Memorial Stadium,

October 24, 1964.

The Bills in the 3-4 alignment with Marty

Schottenheimer (57) in at Right Inside

Linebacker. Versus Miami Dolphins at War

Memorial Stadium, November 10, 1968

There were variations, such as splitting a linebacker out to provide double coverage on a wide receiver to knock him off his route. “We had two defenses that Collier had called for,” Jacobs remembered of preparing for the 1965 Title Game rematch with San Diego. “I put two of those defenses together, and Joe said, ‘Go ahead and do that, practice that.’ What we did is we took the two outside linebackers and put them out on the two wide receivers, and that freed the inside up. And that’s how we shut down Bambi [Lance Alworth]. [The linebackers] didn’t cover him. They were up there to stop him in his footsteps, so the defensive cornerbacks could cover him real well. I called that on most third down situations. And it wasn’t something we’d had before.”

Weak Side Linebacker Mike Stratton split out to

assist with covering enemy Wide Receiver

(Howard Twilley). Versus Miami Dolphins,

September 18, 1966.

A variation on this variation was the “Sloop,” in which a safety moved outside to support a cornerback.

There were “mad dogs” in which the linebackers would shoot a gap in the defensive line, and “fake mad dogs” in which the linebackers lined up as if intending to shoot the gaps but backing off at the snap.

“Exits” were line stunts in which a defensive end would loop around the nearby defensive tackle, who slanted out toward the offensive tackle to occupy his block and potentially confuse the offensive guard.

Defensive End Ron McDole (72) about to perform

a stunt, or "exit" against the New York Jets, 1965.

(Pt 1)

McDole can be seen looping around Defensive

Tackle Jim Dunaway (78), who is slanting across

the line to occupy the Offensive Tackle.

(Pt 2)

McDole is partially obscured by John Tracey

(51) but he is now up against New York Right

Guard, while Dunaway is battling the

Offensive Tackle. This stunt play resulted in a sack

of Jets Quarterback Joe Namath. At Shea Stadium,

October 30, 1966.

(Pt 3)

One of Jacobs’ favorite calls was the safety blitz, most often performed by George Saimes. When run as planned, the safety blitz is a very disruptive tactic.

Free Safety George Saimes blitzing New York's

Joe Namath. At War Memorial Stadium,

November 13, 1966.

PERSONNEL

Starting at the right defensive end was Tom Day. Originally drafted by the Bills in 1960 as a guard out of North Carolina A&T, he opted to sign with the St. Louis Cardinals, who had selected him in the NFL draft. He signed with the Bills as a free agent in 1961 and performed well at the right guard position until Saban moved him to the defensive side in 1964. The move certainly paid off. Tom brought quickness and athleticism to the edge and was known for making tackles on the opposite side of the field because of his speed and hustle. These traits allowed the team’s braintrust to occasionally use Day as a fourth linebacker when the Bills switched to a 3-4 alignment.

Defensive End Tom Day

At right tackle was Tom Sestak, perhaps the defense’s best player. A 17th-round draft pick out of McNeese in 1962, Sestak was a tight end in college. By the time he showed up for his first Bills training camp, Sestak had beefed up so much he was almost unrecognizable to the scouts who recommended him. On a hunch, head coach Lou Saban offered him to Collier, and the rest is history. Sestak was selected an AFL All-Star in his rookie season and would be named First-team All-AFL three times, and Second-team three others. To this day, he is still considered by many historians to be the greatest defensive tackle the team has ever had.

Jim Dunaway (Mississippi) was the left defensive tackle. Listed at 290 pounds, Dunaway was huge for his day and combined his girth with tremendous strength. Those traits were put to good use by Collier, who slid Big Jim every once in a while over to nose tackle in the Bills’ 3-4 alignment. Dunaway earned his first of four AFL All-Star selections in 1965.

At left defensive end was the foreman of the line, 6-foot, 4-inch, 265-pound Ron McDole from the University of Nebraska. McDole was originally drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals of the NFL, where he played one season before going to the Houston Oilers of the AFL. After a single season in Houston, the Bills acquired McDole’s rights and he became a cornerstone player. A real hustler, McDole was at times used as an inside linebacker in the Bills’ 3-4 alignment and was very effective when dropping into coverage. He is credited with 6 interceptions in his 8 seasons with the Bills, still a club record for defensive linemen.

Defensive End Ron McDole

Holding down the left (or strong) side linebacking position was another NFL castoff and former tight end, John Tracey, who set several receiving records while at Texas A&M. The defense’s elder statesman, Tracey began his pro career playing tight end with the Chicago Cardinals in 1959 but was converted to linebacker the following year. After a third NFL season with the Philadelphia in 1961, Tracey joined the Buffalo Bills. He was known for being fast, aggressive and a sure tackler. He also led the Bills in interceptions in 1963 with 5.

In the middle was the universally acknowledged “quarterback” of the defense, Harry Jacobs (6-foot, 1-inch, 226 pounds, Bradley University). Jacobs came to Buffalo in 1963 via a trade with the Boston Patriots, where he had played for Saban and Collier in 1960 when they were coaching the Pats. Often referred to as the Baby-Faced Assassin for his youthful looks, Jacobs pulled a complete Jeckyl-and-Hyde routine once he put his helmet on and entered the playing field.

Middle Linebacker Harry Jacobs

The weak-side linebacker was perennial All-League selection Mike Stratton, a rangy 6-foot, 3-inch, 224-pound former tight end out of Tennessee. Stratton was a consistent performer on the field who possessed great speed and versatility, being equally adept playing against the run or the pass. He is perhaps best remembered for applying the “Hit Heard ‘Round the World” on Keith Lincoln in the 1964 AFL Title Game. He played in his first of 6 AFL All-Star games in 1963.

Linebacker Mike Stratton

At right corner was rookie George “Butch” Byrd, a bruising 6-foot, 211-pounder out of Boston University. Byrd was known for his aggressiveness not only while going after enemy aerials (he led the team in interceptions 3 times and still holds the team record for career interceptions with 40), but also going after enemy receivers. Byrd was one of the most physical corners in pro football back in the day, enjoying the freedom defensive players were given at the time to slam opposing pass catchers as they came off the line of scrimmage.

The left corner position was shared between Charley Warner and Booker Edgerson. Warner came to the Bills late in 1964 and filled in well when Edgerson was knocked out of action, including picking off a pass in the 1964 championship game against San Diego. Lightning fast, Warner’s greatest contribution might have been as the team’s first truly great kick returner. Edgerson resumed his starting role in 1965. Originally signed as a free agent when Lou Saban took over as coach in 1962, Booker was well known to Saban and Collier since he had played for them at Western Illinois. Blessed with speed and smarts, Edgerson is acknowledged by most teammates as having been the best man cover cornerback on the team.

Cornerback Booker Edgerson

The strong-side safety position was essentially split between Gene Sykes (1964) and Hagood Clark (1965). Sykes was a 19th-round pick out Louisiana State in 1963. He picked off 2 passes during the Bills’ first championship season. In 1965, second-year man Clarke (6-foot, 205 pounds, University of Florida) emerged as the starter, and swiped a team-leading 7 passes during the Bills’ successful defense of the AFL crown.

Strong Safety Hagood Clarke

George Saimes, a 5-foot, 11-inch, 186-pound former halfback out of Michigan State, was the team’s free safety. After starting the first couple of games of his rookie season (1963) at halfback, Saimes was permanently converted to safety, where he blossomed into one of the best defensive backs in the league by his second year. He was a fine open-field tackler and always a threat for a safety blitz, inspiring favorable comparisons to St. Louis Cardinals All-World safety Larry Wilson. After intercepting 6 enemy aerials in ’64, Saimes was named to his first of 5 AFL All-Star games.

Free Safety George Saimes

THE GAMES

When Mack Lee Hill of the Kansas City Chiefs ripped off a 53-yard scoring run against Buffalo on October 18, 1964, it was indeed a significant moment, since it was destined to be the last rushing TD the Bills surrendered for over a year. The Bills would not be scored against on the ground for the next 17 consecutive games—16 regular season and 1 postseason.

Game 1 – October 24, 1964, versus New York Jets. Bills win 34-24, allowing the Jets’ leading rusher, Bill Mathis just 34 yards on 12 carries.

Game 2 – November 1, 1964, versus Houston Oilers. Bills win 24-10. The Oilers leading rusher was Charley Tolar, who gained a paltry 32 yards on 13 carries.

Game 3 – November 8, 1964, at New York Jets. Bills win, 20-7. The defense is nearly impenetrable in holding Bill Mathis to 16 yards on 7 carries and Matt Snell to 15 yards on 6 carries! The Jets as a team managed to gain 31 total rushing yards in this contest, the lowest amount given up during the streak.

Game 4 – November 15, 1964, versus Boston Patriots. Bills lose, 36-28, but no one could blame the defense! Boston rusher were stymied at every turn, with Larry Garron pacing the Pats with 21 yards on 10 rushes. Despite giving up 240 yards and five touchdowns through the air, the Bills picked off quarterback Babe Parilli 3 times.

Game 5 – November 26, 1964, at San Diego Chargers. Bills win 27-24. The Chargers’ top runner was Keith Lincoln with 34 yards on 8 carries.

Game 6 – December 6, 1964, at Oakland Raiders. Raiders win 16-13. The Bills gave up 56 yards on 13 carries to Clem Daniels, but still did not allow a rusher to reach the end zone.

Game 7 – December 13, 1964, at Denver Broncos. Bills win 30-19. A total domination as the Bills allow Denver fullback a lousy 18 yards on 7 carries.

Game 8 – December 20, 1964, at Boston Patriots. Bills win24-14. Boston’s leading rusher was Larry Garron, who managed just 26 yards on 8 attempts.

Game 9 – December 26, 1964, AFL Title Game versus San Diego Chargers. Buffalo wins, 20-7. Bills hold the Chargers to 134 total rushing yards, undeniably attributable to Mike Stratton knocking San Diego's star fullback Keith Lincoln out in the first quarter with the tackle known to history as the “Hit Heard ‘Round the World.”

Mike Stratton takes out San Diego's Keith

Lincoln with the "Hit Heard 'Round the World."

AFL Title Game, War Memorial Stadium,

December 26, 1964.

Game 10 – September 11, 1965, season opener versus Boston Patriots. Buffalo wins 24-7. Boston’s top rusher this day was quarterback Babe Parilli, who managed 71 yards on 7 carries while running for his life. Jim Nance, the Patriots’ main running threat, picked up just 17 yards on 9 carries! The Bills defense also picked off Parilli 5 times.

Game 11 – September 19, 1965, at Denver Broncos. Bills win, 30-15. The tough Buffalo defenders were on a mission, holding former Bills running back Cookie Gilchrist to just 26 yards on 12 carries. The Broncos were held to a total of 69 yards rushing on the day.

Game 12 – September 26, 1965, versus New York Jets. Bills win 33-21. The Bills held the Jets to 44 yards on the ground, with Matt Snell leading the Jets charge with 31.

Game 13 – October 3, 1965, versus Oakland Raiders. Bills win, 17-12. Clem Daniels ekes out 55 yards on 16 carries, but it didn’t matter. In fact, the Raiders managed a meager 159 yards of total offense in this laugher.

Game 14 – October 10, 1965, at San Diego Chargers. Chargers win 34-3. The Bills were crushed in the rematch of the previous year’s championship game, giving up 369 yards and 3 TDs via the pass. But the ground defense held firm, a holding the Chargers rushing leaders, Paul Lowe, to just 37 yards on19 carries.

Game 15 – October 17, 1965, at Kansas City Chiefs. Bills win 23-0. Mack Lee Hill gained just 36 yards on 8 carries while Curtis McClinton gained 28 yards on 10 lugs.

Game 16 – October 24, 1965, versus Denver Broncos. Bills win 31-13. Cookie Gilchrist made his return to War Memorial Stadium and picked up 87 yards on 21 rushes, but he didn’t find the end zone!

Buffalo's defense extends its unbelievable string

to 16 games at War Memorial Stadium, versus

Denver Broncos, October 24, 1965. Former Bill

Cookie Gilchrist (2) carries as Buffalo's John

Tracey (51), Hagood Clarke (45) and Ron

McDole (72) close in.

Game 17 – October 31, 1965, versus Houston Oilers. Oilers win, 19-17. The Oilers churned out 124 yards on the ground—the highest regular-season total the Bills allowed during the streak—but the goal line remained undisturbed.

The streak came to an end against the Boston Patriots on November 7, 1965, when J.D. Garrett scored from I yard out. The Bills went 13-4 during that span, scored 398 points (23.4 per game) and allowed 285 (16.8 per game). The funny thing is that the team did even better in those two championship seasons in the 13 games before and after the streak. Combined, Buffalo recorded an 11-1-1 mark in the 13 non streak games, averaging 30.2 points per game and giving up just 14.6.

The run of 17 straight games without giving up a rushing touchdown is a record (going back to 1940) that still stands. The streak was threatened by the Chicago Bears great defense of 1986-87, but they only managed to get to 16 games. Long live the Streak!

Komentar

Posting Komentar